Double Indemnity: A Femme Fatale, a Naive Salesman, and a Pact with the Devil

The mean streets of Hollywood, 1944. A man walks into an office bleeding from a gunshot wound and starts a confession. He’s telling the story of a dame rotten named Phyllis Dietrichson. She’s got an ankle bracelet and a look that could melt a glacier, and she just sold him on a one-way trip to a very special kind of hell. This is the world of ‘Double Indemnity,’ a film that didn’t just define the noir genre; it was a shot across the bow of American cinema, a story so cynical and so hard-boiled it made every other crime picture look like a Sunday school picnic.

A Masterclass in Deception

Directed by the great Billy Wilder, with a script co-written by the equally great Raymond Chandler, this film is a clinic in how to build tension. The plot is simple, a crime of opportunity that spirals into a tragedy. Insurance salesman Walter Neff (Fred MacMurray) meets the seductive Phyllis Dietrichson (Barbara Stanwyck) and a plan is born: kill her husband and collect on the ‘Double Indemnity’ clause of his life insurance policy. But in the world of noir, a simple plan is a fool’s errand. The moment they shake on it, the walls start closing in.

The film’s power comes from its performances. Fred MacMurray, known for playing everyman characters, is a revelation as the weak, lovestruck dope who thinks he can outsmart a cold-blooded killer. His voice-over narration, dripping with a fatalistic world-weariness, is the sound of a man digging his own grave with every word. Barbara Stanwyck, a true icon, plays Phyllis with a chilly, calculated menace. She’s not a woman; she’s a predator, a cold drink of water in a hot room. And then there’s Edward G. Robinson as the dogged claims adjuster Barton Keyes, a loyal friend with a nose for fraud that could smell a lie from a mile away. He’s the moral compass of the film, the one man who refuses to believe in the perfect crime.

The Cinematography of Shadows and Sin

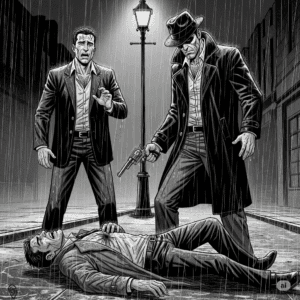

Beyond the story, ‘Double Indemnity’ is a feast for the eyes. Cinematographer John F. Seitz blankets the film in a shroud of shadows and cigarette smoke, with light filtering through Venetian blinds like bars on a prison cell. The Dietrichson house feels like a cage, and the back alleys of Los Angeles are a dark labyrinth with no way out. The atmosphere is so thick you could cut it with a knife. The film is a textbook in visual storytelling, where every shot, every long shadow, and every close-up of a sweaty face is meant to convey the mounting paranoia of its characters.

The romance between Neff and Phyllis is a twisted, fatalistic affair. They are drawn to each other not by love, but by greed and a shared contempt for the world. Their love story is a suicide pact, a slow-motion car crash that you can’t tear your eyes away from. In the end, there is no escape, no redemption, and no happy ending. The film is a stark reminder that some sins are paid for not with money, but with blood.

Final Verdict: The Quintessential Noir

In the end, this is a picture that gets everything right. The dialogue crackles with sardonic wit, the plot zips along at a blistering pace, and the final moments hit you like a punch to the gut. ‘Double Indemnity’ is more than just a crime film; it’s a study of moral decay and the seductive nature of evil. It’s a gold standard, a masterpiece of the genre, and a hard-hitting reminder that when a man signs a pact with a beautiful dame, he’s probably signing his own death warrant.